Ted Geoghegan’s chamber horror drama “Brooklyn 45” takes place one fateful night in 1945, and focuses on a small gathering of gruff veteran friends in the parlor of one Lt. Col. Clive Hockstatter (Larry Fessenden). Also known as Hawk, Fessenden’s grieving character needs their help holding a seance, so he can reach his departed wife, who died by suicide and deeply believed Nazi spies were in her neighborhood. Such an intense experience becomes personal and frightening for all, as their paranoias and darkest wartime shames bubble to the surface, with Geoghegan’s lovingly constructed and flawed characters forced to face the hate-driven horrors they have wrought overseas.

“Brooklyn 45” was shot all on a soundstage outside Chicago, and displays Geoghegan’s savvy eye for the character actor performance. His cast is comprised of sneaky heavyweights, starting with an incredibly raw Fessenden, who rarely gets this much screen time or narrative power. Fessenden is joined by the memorable mugs of Ezra Buzzington, Anne Ramsay, Jeremy Holm, Ron E. Rains, and Kristina Klebe, who make “Brooklyn 45” an emotionally charged and dramatically surprising film that circles the question of what makes a bad person.

Geoghegan’s previous directorial efforts are the supernatural chiller “We Are Still Here” and the tense chase movie “Mohawk,” which was set in 1812. “Brooklyn 45” premiered at this year’s SXSW Film Festival, along with “Molli and Max in the Future,” which he produced.

RogerEbert.com spoke with Geoghegan about making “Brooklyn 45,” collaborating with his veteran father on the screenplay, the power of character actors, and more.

It’s got to be a huge filmmaking change to go from shooting an action movie in the woods to setting a dialogue-driven mostly in one room. Was “Brooklyn 45” more or less daunting than “Mohawk”?

Much less. [Filming] “Mohawk” was one of the single most difficult experiences of my life. I’m very proud of the finished film. But it was made in the middle of the hottest summer in years, with everyone wearing wool literally in the middle of nowhere, just slogging the equipment. “Brooklyn 45” was a very contained, intimate setting of a parlor shot on a soundstage. We had complete control over everything. It was such a joy.

Was there any worry or a problem about having people in a room? How did you feel more confident about using more restricted action?

I got to set every single day and was terrified that the movie was going to become boring that day. I am so glad I did that because it made me want to keep that from happening. Every day we fought against our chamber piece being boring.

I will also say that I directed the film like a stage play, and every single day I had very specific movements for all of the actors. I gave them a little index card, and I called them their dance cards, and it showed them where they would be moving that day. The card was a map of the room. I had to keep extremely tight reins on where everyone was in the room, because I needed them to be in certain places at certain times, and it was important that they found their way to those spots organically.

It was sometimes daunting to the actors when they would get their dance card for the day, and it would just have a little dot on it. Like, oh, I don’t move? It was challenging for the actors, but I think it was a fun challenge, for them to go like, OK, I can’t dance around the room today, so what can I do to make my performance interesting as I stay in this singular spot?

Given how wordy this period project can be, how did you figure out how to give us enough information in dialogue, but keep it natural?

I went out of my way to make sure that the dialogue felt organic, not just the 1940s but the modern ear. I didn’t want to have anything anachronistic in the film. So it was a matter of going through every sequence and going, Where are appropriate spots for me to use 1940s vernacular? Where can I use this silly slang? Like, “She’s on the beam.”

I saw that your father has a special thanks in the end credits. How did he support you on this project?

I worked very long and hard on this screenplay and collaborated on it with my father. When I started writing this, I knew this was going to be a period piece, because I never want to make films set in the present. I was very excited about the idea of setting it in the earliest portion of post-war America, right when the war ended, the first few months after World War II. Most people, when they think of post-war America, think of the sailor kissing the girl in Times Square, everyone moved to the suburbs, they had 2.5 children, and then it’s “Leave it to Beaver.” Where in fact, post-war America, especially the first few months of it, were really nightmarish. Suicides were at an all-time high; people were coming back from the war just shells of the people they were when they left. And they were experiencing something the United States had not experienced in a long time, which is double veterans, which are soldiers, generals, sergeants, and majors who fought in both World War I and World War II. Although it’s not expressly stated in the film, all of the characters in my film are double veterans, just based on their age alone. These are men and women who would have fought, sadly, in both wars.

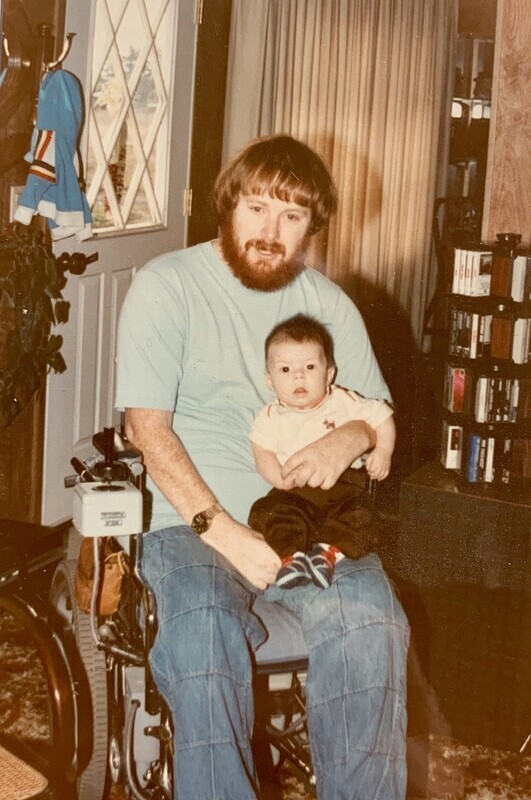

I started writing it, and I got to the end of the first act. And I knew where I was going to go next, but I couldn’t get it there. So I reached out to my father, a retired Staff Sergeant in the US Air Force, and he served for several years before getting into an accident in the early ‘70s and became a quadriplegic. After my father was paralyzed, he went back to school and got his degree in 20th Century US history. And I thought, Who better to ask about this? And he said, “This character wouldn’t be a colonel, they’d be major. This character wouldn’t have been in this battle, it’d be this battle.” Just going through it and ensuring that everything was accurate, not just to his own military experience but his expertise in US history. As soon as he gave me those notes, the whole screenplay just came to life. All the characters suddenly were alive, they had motivations, they existed. The rest of the screenplay just flowed out of me, and I got the rest of the script done in a week.

We bounced the screenplay back and forth, I think six or seven times. He called me up in early January 2019 and said, “It’s done. I’m so excited.” And I jokingly said, “Do you want a co-writer credit?” He said, “No, that’s embarrassing, I just gave you notes.” I said, “Well, OK, I’m gonna give you a special thanks.” And he said, “OK, great, I can’t wait to watch this movie.” And I said, “I can’t wait for you to see it.” And we hung up the phone, and he died. It was the last conversation I had with my dad. I didn’t realize just how personal this project was going to get when that happened. Suddenly I realized I would have one opportunity in my whole life to make a movie with my dad, and this was it, so I really didn’t want to f**k it up.

I was so passionate about what my dad and I had created together that “Brooklyn 45” actually went to several production companies who said, “It’s great, but we’d like to include this, this, and this.” And I said, “No.” And when Shudder came across it and read it, they said it was really good. And I said, “I’m sorry to say this, but I’m not changing a thing.” Because no note that anyone gives me is more important than the work I did on this with my dad.

Was there a certain character that he was drawn to or that we can see the most of in your final product?

He gave notes on everyone. But I think … I am very political, and my movies tend to have my politics in them. And this is a film that is actually quite apolitical. The film itself never condones or demonizes any of these characters. They have their own feelings about each other, but the movie never explicitly states this guy is good, this guy is bad. My father was very passionate about that because, knowing that I am very liberal and a pacifist, he said, “The film should appeal to you and people like you, but it should also be a film that veterans and people who served and people on the right can watch and have a dialogue about as well.” There are few things that the left and the right can agree on, but one of the things that most of them agree on is war is hell. And regardless of how you feel about war, everyone agrees that when you come back from it, you are broken, and you are changed.

Regarding Jeremy Holm’s character, Archie Stanton, he has done something prior to the events of the film that are monstrous. He did them in a moment of weakness, and panic, and people barking orders at him to do something. And clearly, this has haunted him. And definitely, the concept of this character and how he looks at what happened was very much shaped by my dad being in the VA hospital after his accident, and being surrounded by people who were also paralyzed, but during service in Vietnam. People screaming and crying themselves to sleep at night about the atrocities they committed, that they were going to hell, and that they were horrible people. My father would lay in bed, not being able to see these people, just hearing them in the next room, across the curtain. And my dad would ask them, “What did you do?” And they’d say, “Well, I can’t tell you because if you knew, you’d never speak to me again.”And my dad was like, “Well, I want to know. If you tell me, I’ll listen to you.”

It really begs the question: Is a good person defined by a lifetime of good deeds or one good deed? And is a bad person defined by a lifetime of bad deeds or one terrible decision? That’s really one of the big topics that over-arches the whole film, and it never gives you an answer—far from it. I think that was my dad’s fingerprint there, saying there is no answer to this. Some of these people are absolutely bad people. And some people aren’t bad people; they did a terrible thing, but they are not a bad person. But it’s not up to me to brand them one way or another, everyone’s going to have their own opinion on it.

Did you get a lot of empathy from your dad growing up? Do you feel like your dad was a huge influence on that?

Both my parents had a lot of love. When my father was paralyzed in the early ‘70s, he and my mother had been married less than a year, and they remained happily married until my father passed away in 2019. My mother spent decades caring for my father. Just being around that sort of care and empathy very much shaped me.

But at the same time, I’m the first to admit I’ve got my problems, too; we all do. And I think that’s one of the big messages of this film. I personally am drawn to the character of Archie for a number of reasons. He’s such a complex character, and I think Jeremy Holm’s performance is really fantastic. But one of the things that I really like about the character is that he’s a queer person, a closeted gay man in the 1940s. And the fact that he has all of this baggage, all of this grief, and none of it has to do with him being a gay man.

I think representation is so important in the arts, and it’s nice to see the industry realizing that, and we are seeing people of color being represented, and different genders, sexual identities, different orientations. But I think it’s also important we remember that representation doesn’t just mean golden gods. As a bisexual person, one of my favorite pieces of entertainment in the past few years has been James Gunn’s “The Peacemaker,” with John Cena playing this absolute train wreck of a bisexual man who is not defined by his sexuality but is still totally fine with it. You know what it isn’t a mess? His sexuality. I think it’s very important that we see ourselves in our art and that queer people don’t see perfect queer people all the time. We need to see those imperfections. Archie exists for so many reasons, not the least of which is to say that you do realize a gay person can be pushed so far that they can make a terrible decision too. We are all just as fallible as each other.

Larry Fessenden’s monologue at the end of the first act is incredible. What did you talk with him about, and how did you help him find that character?

I wrote Hawk for Larry. Larry is a very close friend of mine, and he’s also a mentor. I wrote the role in “We Are Still Here” for him because I was sick of watching Larry Fessenden get underutilized in cinema. He’s in a dozen movies a year, but if you add up all his time in those movies, you’re lucky if you get two minutes of Fessenden, when he is this phenomenal powerhouse of an actor.

He was definitely caught off guard that he had a six-page monologue, a beast of a monologue. And it really runs the gamut of emotion from self-effacing humor to anger to absolute breakdown sadness. We shot that monologue eight times to get it from every angle, and the fact that Larry was able to go all the way to the dark place where the monologue ends and then restart and do it again is just incredible.

We talked a lot about it, but ultimately it came down to me trusting Larry as a friend and as a performer. I had so few notes for him when he was doing that scene. I think he is such a hidden gem, and with films like this and “We Are Still Here” and Travis Stevens’ “Jakob’s Wife,” I hope more cinema like this reminds people that character actors don’t just have to be in movies for a few minutes.

With this film and your previous projects, you have such a good eye for finding memorable faces. What’s your intuition when it comes to casting?

I love working with character actors because they are so emotive, they are so expressive. They’re such a hidden weapon in cinema. You can get performances out of a look from a character actor that a leading man or a leading woman would have to fight for in another piece of art. I only want to work with character actors, and I’ve done a lot of it in my films both as a director and a producer. There’s a certain acting style with character actors that is the art of being big without being big.

Ezra can say so much with just an angry little glare. And even Ron E. Rains, who plays Bob, plays The Onion’s fictional film critic, Peter Rosenthal. And he is hilarious. And he’s this celebrated stage actor in Chicago, everyone seems to know him from the Christmas Carol in Chicago. What a joy to be able to give him his first major role in a film and just watch him absolutely crush it. He’s able to give Bob these nuances that come from a history of comedy and stage acting that land so powerfully.

Given the personal history behind this film, how do you feel about it now that it’s about to be shared with the world?

My takeaway from his film is that I don’t really give a shit what other people think about this movie anymore. I actually really care about what people think about “We Are Still Here” and “Mohawk” to this day. “Brooklyn 45”? I love it. I know this movie has to be successful, but the truth is, if people don’t like it, that’s on them. And that’s a really nice feeling to have after 22 years in this industry. Even if I don’t believe in the afterlife—I don’t believe my father is on some cloud watching this movie—it’s a movie that I feel like he would have been proud to have his name on.

“Brooklyn 45” is now playing on Shudder.